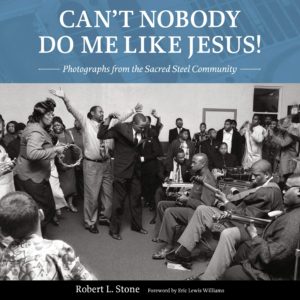

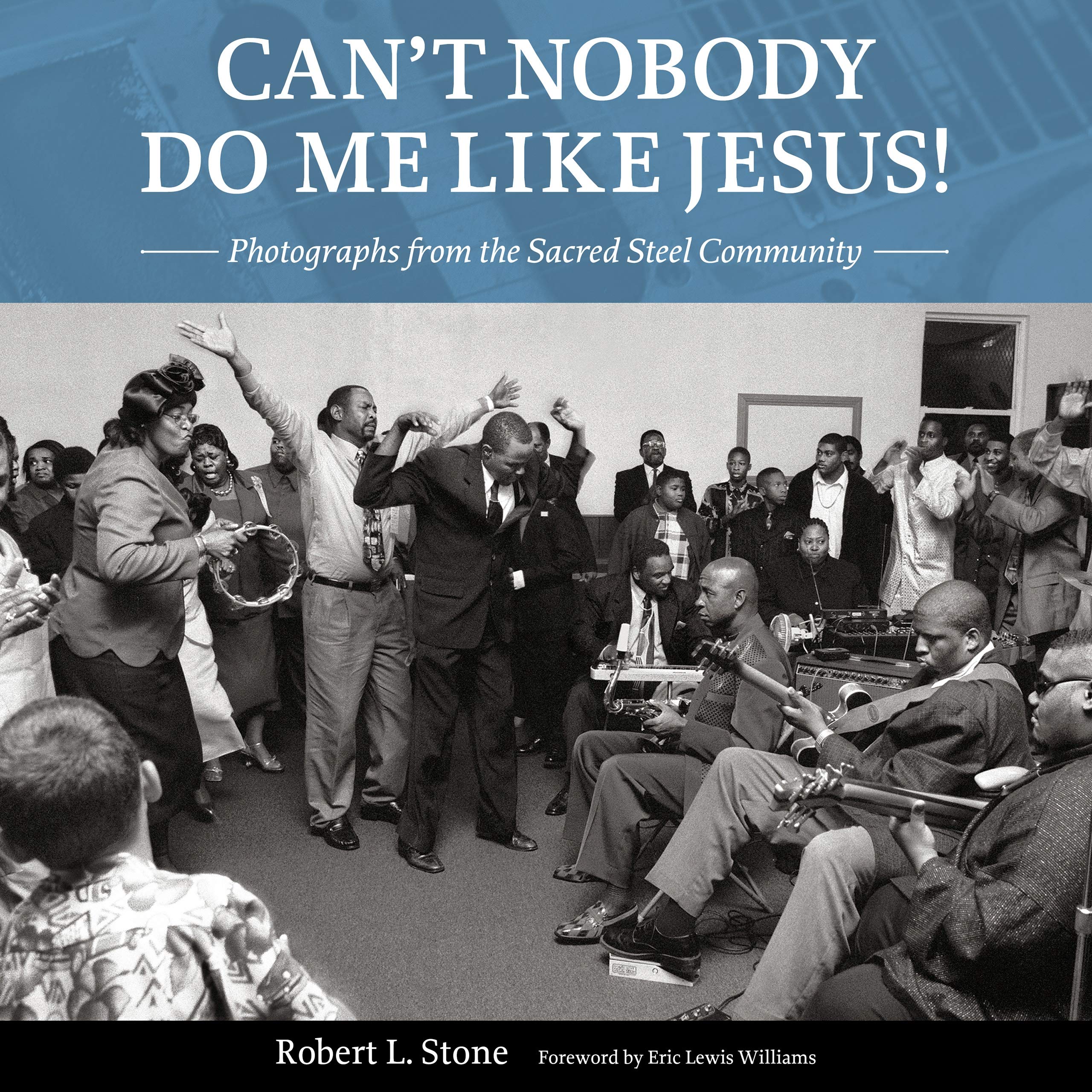

Can’t Nobody Do Me Like Jesus! Photographs from the Sacred Steel Community. By Robert L. Stone. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 192 pp. (hardcover). Illustrations, Extended Photo Captions, Notes. ISBN 978-1-4968-3150-7. $40.00

Can’t Nobody Do Me Like Jesus! Photographs from the Sacred Steel Community. By Robert L. Stone. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 192 pp. (hardcover). Illustrations, Extended Photo Captions, Notes. ISBN 978-1-4968-3150-7. $40.00

By Robert M. Marovich

With Can’t Nobody Do Me Like Jesus! Florida historian and folklorist Robert Stone presses into place the final puzzle piece of his years’ long audio-visual portrayal of the House of God and Church of the Living God steel guitar tradition. Having written Sacred Steel (University of Illinois Press, 2010), the definitive history of these Holiness churches’ distinctive music ministry, and produced, with support from the Arhoolie Foundation, several CDs of the music’s top stylists and a video documentary, Stone brings the verve of the churches to life in a handsome photographic essay.

Gospel music enthusiasts just learning about the House of God and Church of the Living God’s steel guitar tradition can best understand its role by comparing it with the Hammond organ. Both are essentially instruments of the twentieth-century. Both have the capacity to emulate a myriad of vocal sounds and emotions, from sadness to indescribable ecstasy. In Holiness and Pentecostal churches, where a personal encounter with the Holy Spirit is the apex of the worship experience, steel guitar and Hammond B3/Leslie speaker alike serve to convoke and celebrate the Spirit. Viewing the photos in Stone’s new book, one can almost hear the searing treble notes plucked by the pedal and lap steel players resounding off the church walls.

But the book is not just about the music. It describes in words and images the churches’ practices and the meaning behind them. The book opens with a concise history of the birth and split of the House of God (Keith Dominion) and Church of the Living God (Jewell Dominion), and how the steel guitar came to be used in the service of worship. Each chapter or section introduces what the reader is about to view. Those who haven’t read Stone’s Sacred Steel will glean a workable understanding of the churches and their music traditions from the Introduction and each section.

Most interesting is how the churches’ declaration to be in the world but not of it has kept, until recently, the sacred steel tradition just that—sacred. Like the shout or trombone bands of the United House of Prayer for All People, steel guitar as worship music is the product and possession of its congregations. After all, the church is the one place where African Americans are free to express themselves without enduring the exploitative or critical eye of the wider populace. However, as Stone notes, folk festivals and the few celebrity steel players like the Campbell Brothers and Robert Randolph have helped move the sacred steel sound outside of the churches, though without in any way lessening its profound importance to the community that gave it birth.

In addition to photos of the musicians engaged in ministry are portraits of the genre’s revered pioneers and top players. Willie Eason’s photographic images capture the easy ebullience of a man seemingly in perpetual motion. The loss of some of the steel guitar artists portrayed is palpable, especially in the essay on funerals, which covers the homegoing of steel guitar legends Glenn Lee and Henry Nelson, the latter laid out with his finger picks.

In the Introduction, Stone describes how he developed the trust of his photographic subjects and followed the churches’ cues as to what was and was not appropriate to photograph. The churches gave their imprimatur on the images before they were published and Stone was ultimately adopted into the royal family of the churches. His intention was to ensure that the essay was presented with respect and not with the exoticism of some other photographers’ portraitures of Holiness and Pentecostal churches. The dignity with which Stone approached his work is even evident in the quality of the physical object itself—the hardcover binding and cover slip, the quality glossy paper, and the crisp high-resolution images, which are worthy of a gallery exhibition. As such, the book is a primer for anyone seeking to explore the traditions of a community with which he or she is not an active participant.

Can’t Nobody Do Me Like Jesus! is a living history of a vibrant music with deep roots in African-American worship. Robert Stone, foreword contributor Eric Lewis Williams, the University Press of Mississippi, the Arhoolie Foundation (which supported this project), and all those who consented to be photographed, offer a masterful and visually delightful survey of an enduring American art form. If you miss church one Sunday, don’t despair; you will find spirituality aplenty by spending an afternoon with this book.

Five of Five Stars

One Comment

Leave A Comment

Written by : Bob Marovich

Bob Marovich is a gospel music historian, author, and radio host. Founder of Journal of Gospel Music blog (formally The Black Gospel Blog) and producer of the Gospel Memories Radio Show.

Visit Today : 10

Visit Today : 10 This Month : 255

This Month : 255

That’s my Uncle!!